The most commonly used marker for how the body responds to training is changes in heart rate, mainly resting heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) (how much variation there is between each beat in your heart rate). These measures have been used for decades by researchers, coaches, and athletes. Originally this was because heart rate was one of few objective measures that you could easily obtain. In short, a lower resting heart rate and a higher heart rate variability are taken as indications of positive responses to the training, and the opposite direction is considered a sign of [too] hard training. While this might be true for the average, the reality is far more complicated, and it is crucial to understand the individual responses.

The heart has its own pacemaker cells which, unaffected, make it keep 90-110 beats per minute. To respond to external demands like exercise, stress or complete rest, the heart interacts with the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic system is usually described as the fight or flight system and increases heart rate. The parasympathetic system is the rest and digest system which decreases heart rate. If a dangerous situation occurs, the sympathetic system responds quickly, and your heart rate can go from 50 to 120 bpm or so within seconds to liberate the energy reserves needed to take care of the situation.

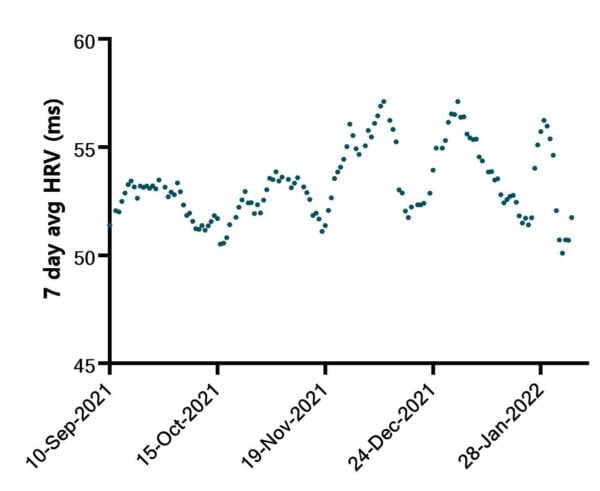

In our work we follow athletes over time and we find that, in addition to the short term responses described above, the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are rhythmically activated and inactivated over much longer periods, with a frequency of anywhere between 6 to 20 days. This can be seen in the chart below for an example athlete:

This means that a healthy nervous system will switch between being in a low grade fight or flight mode for anywhere between 3-10 days and then go into rest and digest mode for about the same length of time. Some athletes notice this pattern clearly and can feel very energetic and able to push hard in training during the fight or flight period and then go into recovery mode, whether they like it or not. For others the effects are more subtle. We are just beginning to understand how training and recovery should be adjusted during the different phases to be more in tune with the state of your nervous system.

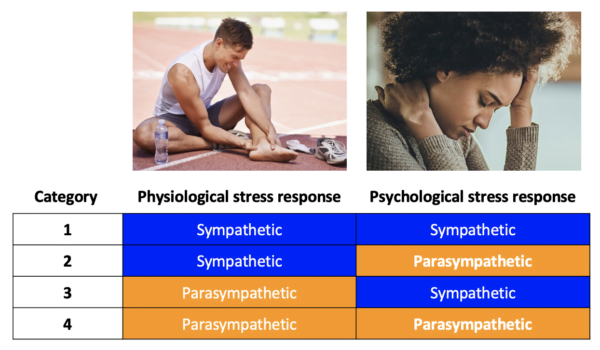

To gain an understanding of different individual response patterns, we measure resting HR and HRV during sleep, using for example Ōura rings or smartwatches, at the same time as tracking training load using HR-data or GPS-tracking. In addition, subjective ratings of physical, emotional and psychological status are collected on a daily basis using our Athlete Advisor application. We find that only about 1/3 of athletes respond according to the textbook with a decreased resting HR and increased HRV after increases in training load. Another 1/3 does not show any significant changes at all and the last 1/3 actually respond with an ‘opposite to textbook’ increased resting HR and decreased HRV after increased training loads. No wonder the field is regarded as “inconclusive” in the scientific literature! Despite these fundamental differences between individuals, the same individual seems to respond in about the same way over time. When we looked at the response to psychological stress, we found the same pattern with 1/3 showing an activation of the sympathetic system, 1/3 did not respond at all and 1/3 showed an activation of the parasympathetic system. We could thereby categorize the athletes into four different profiles depending how they responded to psychological or physiological stress:

Athletes in category 1 respond with sympathetic activation to both psychological and physiological stress. Whereas athletes in category 4 respond to both types of stress by activating the parasympathetic system. During times of both high psychological and physiological stress athletes in category 1 are likely to suffer from sleep disturbances, weight loss, high resting and exercising heart rate. Athletes in category 4 are more likely to respond to the same situation with lack of motivation, depressive thoughts, weight gain, and lower heart rate during intense exercise. Our interpretation of the non-responders is that they did not experience any stress that was large enough to invoke a response in any of their systems. After all, this is observational data and it is logical that these individuals will show a response if they encounter a significant stressor.

Conclusion: Elite athletes experience both immense physiological and psychological stress during training and competitions, and knowing how their individual nervous system responds to different types of stressors can help each athlete and their coaches to better tailor their training plans around stressful periods and in the build-up towards major competitions.